See our earlier article on the processes that we developed at Pathomation to improve our software development practices.

Software validation

Much has been written about software testing, verification, and validation. We’ll spare you the details, subtleties, and intricacies of these. Fire up your favorite search engine. Contact your friendly neighborhood consultant for a nice sit-down fireside chat on semantics if you must.

Suffice it to say that validation is the highest level of scrutiny you can throw against your code. And, like many processes, at Pathomation, we take a pragmatic approach.

Pragmatic does not need to mean that we bypass rules or cut corners. Au contraire.

The need

The process sometimes gets a bad rep. If software validation is so involving, why even do it at all? After all:

- You have a ticketing system like jira or Bugzilla in place, right?

- You have source code control like git or svn in place, right?

- Your developers can just test their code properly before they commit, right?

- Right?…

Anybody with any real-life experience in software development knows it’s just not that simple.

At Pathomation, we have jira; we have git; we add Slack on top of that for real-time communication and knowledge transfer; etc. And yet, there was something missing.

Consider the following typical problems during non-validated SDLC:

- Regression bugs

- Incorrect results

- Wrong priorities

- Bottlenecks and capacity planning problems

Are you rolling your eyes now and thinking “Du-uuuuh”? Do you think these are just inherent to software development in general? Well, let’s see if there’s a way to reduce the impact of these at least a bit.

GAMP

Writing software is sort of like a manufacturing process. So with terms like GLP (Good Lab Practice) and GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice) already in existence, it made sense to expand the terminology to GAMP, which stands for Good Automated Manufacturing Process (and yes, is derived from GMP).

In essence, GAMP means that you’ve documented all the needs that your software addresses, have processes in place to follow-up on the fullfillment of these needs (the actual code writing process), and subsequently have a system in place to provide that the needs are effectively met.

GAMP helps organizations to prove that their software does what you say it does.

There a different levels of GAMP, and as the levels increase, so does the burden of proof.

- Gamp levels 1-3 are reserved for really widespread applications. Think about operating systems and firmware. When you install Windows on a server, you expect it to do what it does. You may still check out a couple of things (probably specific procedures tied to your unique situation), but roughly speaking you can rely on the vendor that the software does what you expect it to do, and that bugs will be handled and dealt with accordingly.

- Gamp level 4 is tied to software that can still be considered COTS, but is somewhat less widespread than, say, an operating system. It may be an open source application that you think is a good fit in your organization: it may have a wide user base, but it’s hard at the same time to beat the resources of the big tech companies. A certain level of scrutiny is still warranted.

- Gamp level 5 is for niche software applications. It requires the highest level of checks, tests, and reporting. To some extent, everybody that builds their own software (including the big techs) is expected to do their own Gamp 5 validation.

We like to brag that we see a lot of users. But regardless how many satisfied users we have, we’ll never come even close to software that has the user bandwidth of Microsoft Office, Google Chrome, or even specialty database management systems like MongoDB or Neo4J.

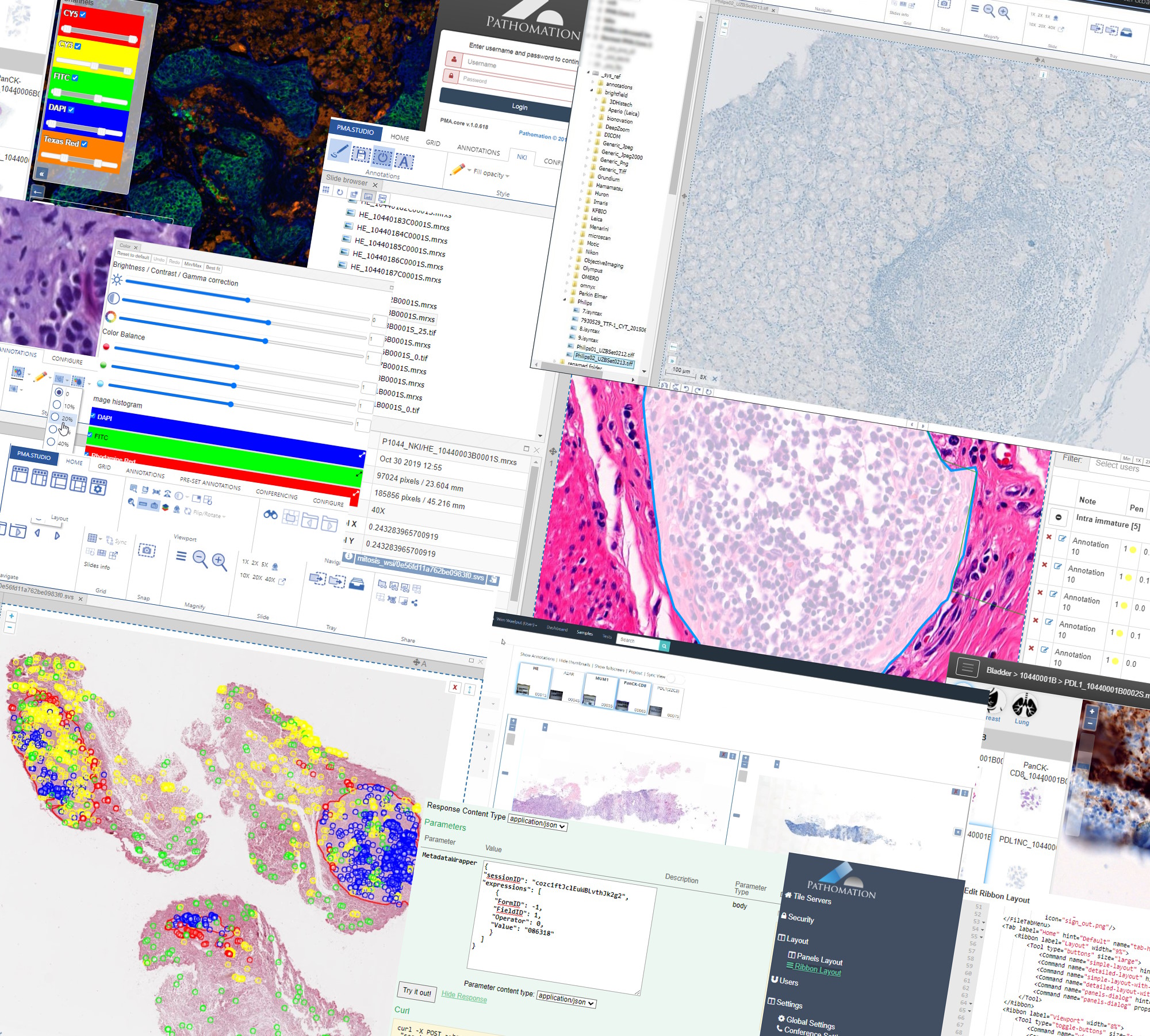

PMA.core (including the PMA.UI visualization framework) is niche and custom software. Therefore, all of its derived components must go through extensive Gamp 5 validation procedures.

Next stop: Amazon. Read instructions. Clear.

Hard times and manual labor

In principle, it’s all very simple: you document everything that you do and provide evidence that you’ve done it, and that at the end of the day things work as planned and expected.

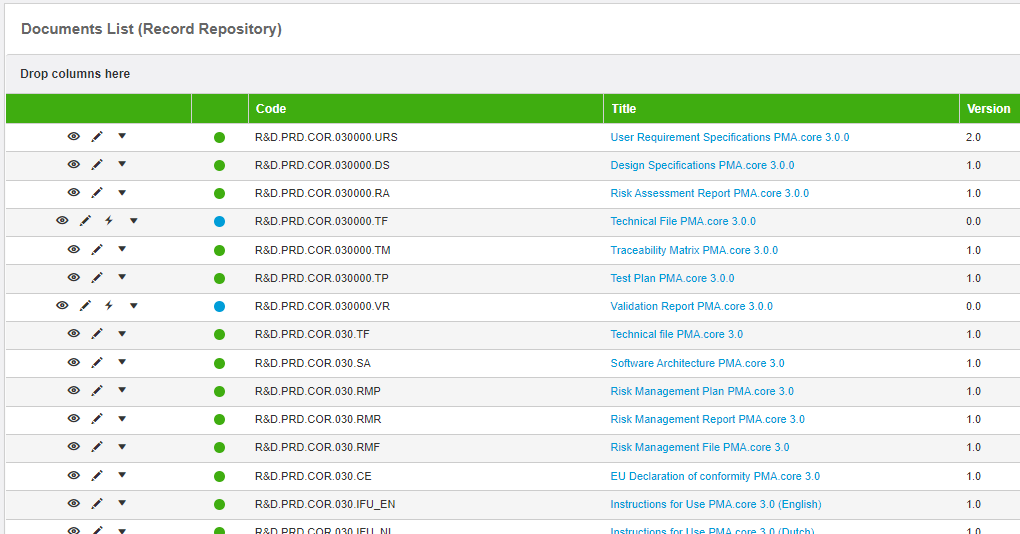

But at the very least, you need somebody to monitor this entire process, and, most importantly: keep it going. So we did contract with an external organization, and it sort of worked. That is, after a lot of frustration, we ended up with a list of documents that was good enough to claim that version 1.0 of our software was now validated:

The experience was not a fun one; nor a creative one; nor a productive one; nor… There were many things it wasn’t. In typical Pathomation (remember, we’re rebels at heart) we started wondering how we could improve the process. We identified two major bottlenecks:

- Lack of involvement: it’s all too easy to throw money at a problem hoping that it will go away. It doesn’t. Read our separate rant about consultants for a somewhat different perspective on the consultancy world.

- Inefficient procedures. No, wait, that’s too polite. How about hopelessly obsolete antiquated workflows? Getting there. Except for the word “flow”. What we did; it didn’t flow at all; think of molasses flowing; or lava…

Essentially we ended up sending back and forth a bunch of Word document. A lot of them… and they were long…

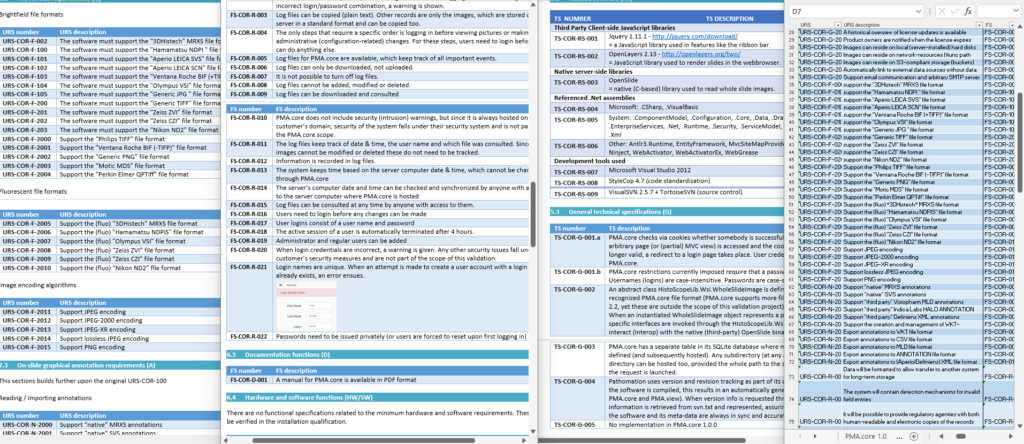

And you dread the moment when you want to add anything afterwards, because that involves making modifications in long documents that all need to reference each other correctly. Like below:

A user requirement specification (URS) needs to have functional specifications (FS), followed by technical specifications (TS). Since the all these are spread out across separate Word documents, you need a fourth document to track the items across the documents; a traceability matrix (TM). The TM is stored as an Excel spreadsheet, because stored tables in a Word document would just be silly… apparently??

They say insanity is repeating the same process over again and expecting different results, right? That was our conclusion after our first couple of iterations and experience with the software validation process as a whole.

A tunnel… with light!

Realizing that we would first and foremost have to take more ownership of the validation process, we thought about tackling the “not a fun one; nor a creative one; nor a productive one” accolades. Pathomation is an innovative software company itself. Could we put some of that innovation and software savviness into the software validation process itself, too?

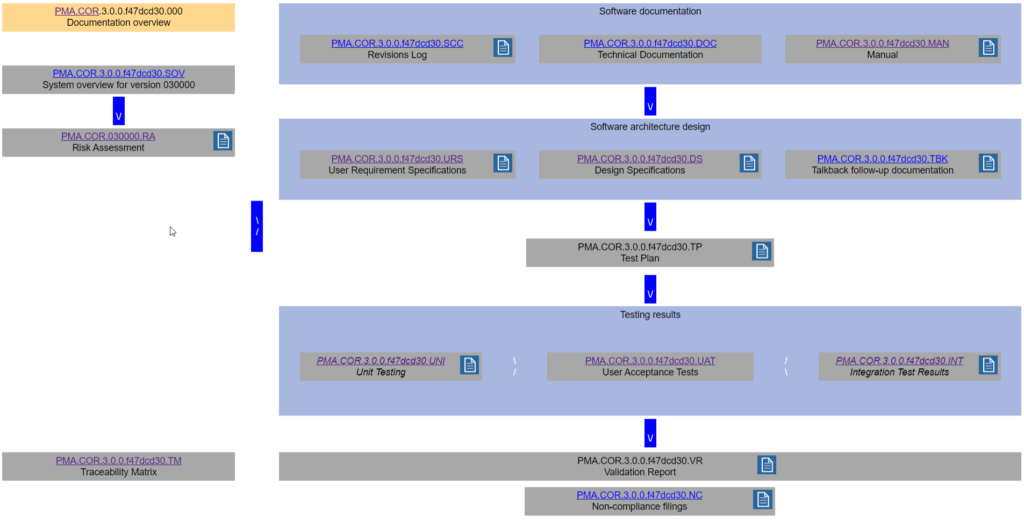

We started by looking back at the delivered documents from our manual procedure. After some doodling on paper, we deduced a flow-chart that we agreed would be pretty much common to each validation project:

Our 30k view in place, our next step was to start thinking about what the most efficient way could be to fill it our for new products and releases going forward. That is the story we’ll be elaborating on in part 3 of this mini-series.